| Development

of Ancient Egyptian Art |

Egyptian

Art

The

aesthetic qualities of ancient Egyptian art are greatly admired

in our modern day and age, however the concept of art for

art's sake was non-existent in ancient Egypt. Although the

Egyptians did aim for great aesthetic levels in their art,

they did not create masterpieces for the simple pleasure of

admiring them. Egyptian art was, for all intent and purposes,

a religious and funerary art that played a significant part

in the cult of the gods and the dead. The magnificent art

pieces displayed in museums across the world are now out of

their original context and, understandably, it is sometimes

difficult to understand their significance. Colourful paintings

and reliefs, which once decorated the walls of tombs of Pharaoh

and the royal family, wealthy officials, courtiers, and nobles,

ensured the survival of the deceased in the afterlife. Sculptures

could serve as a home for the " kÔ " of the deceased (his

spiritual essence) while others would be ex-voto and gifts

offered to a deity. Some statues were even the manifestation

of gods residing in a temple, where priests performed daily

rituals and saw to the well being of the god.

|

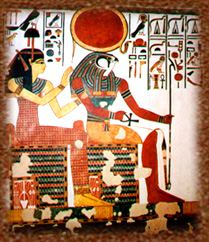

Hathor

and Re-Horakhty from the tomb of Nefertari from the

19th Dynasty found in Facsimile of Nefertari's tomb

paintings in the Harrer Collection, San Bernardino,

California

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

Although

the Egyptians expressed themselves and their culture in many

artistic ways, the present text deals solely with the so-called

"major arts" : sculpture, painting, and sculptured relief.

Architecture, which is also one of the major arts, will not

be discussed here since it is rather lengthy a topic. Painting

and sculpture are two artistic expressions with which all

are familiar, however, the principle of sculptured relief

might be foreign to many. Sculptured reliefs, in very simple

words, are basically drawings that have been carved on flat

surfaces, stone walls and slabs being the prominent surfaces.

Once the desired figure has been drawn on the wall, the artist

can remove a thickness of the flat surface around the figure,

giving the impression that the figure sticks out from the

wall. Such type of relief is known as "raised relief." On

the other hand, if the artist carves the contours of the figure

and the figure itself really deep into the wall, the illusion

of the figure being embedded in the wall is created. This

is called "sunk relief." Sunlight dance and play with the

carvings, thus creating shadows that give the reliefs a certain

fullness and roundness impossible with pictures simply drawn

on a wall. Such is the beauty of sculptured reliefs.

|

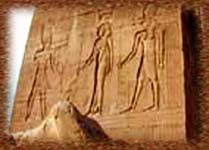

Sunk Relief from a temple at Denderah

from the Graeco-Roman Period found in Denderah

|

Credits: Egyptvoyager |

Development

of Ancient Egyptian Art

Ancient

Egyptian art, like any other artistic expression of a given

period, reflected the social and cultural milieu from which

it emerged. Additionally, the physical and geographical environment

played a major role in the initial development of what may

be define as typical Egyptian art.

A

quick glance at a geographical map of Egypt reveals a country

bordered by fantastic natural frontiers.

|

|

The

northern border was the Mediterranean Sea, a formidable body

of water, which only the most adventurous merchants would

dare cross. The Sahara Desert (also called the Western Desert)

separated Egypt from its western neighbour, Libya. Another

desert, the Eastern Desert, which the Egyptians believed was

filled with monsters, stretched between the Red Sea Coast

and the Nile Valley, creating the eastern border. South, the

Batn el-Haggar (the Belly of the Stones), a most desolate

and arid region between the Third and Second Cataracts of

the Nile River, in Nubia, was another excellent natural border.

In addition to the Batn el-Haggar, the numerous cataracts

on the river made sailing into Egypt from the south extremely

perilous.

Although

arid deserts, dangerous seas, and cataracts surrounded the

country, Egypt was nevertheless a very fertile and promising

land. The regular and predictable floods of the Nile River

left a thick black silt that fertilised the land, thus allowing

peasants and pastoralists to settle in the valley and prosper.

Moreover, within the boundaries of Egypt, the Nile is free

of cataracts and thus navigable. Egypt was truly the 'gift

of the Nile'. Such geographical isolation and luxurious environment

resulted in a self-reliant and self-sufficient civilisation.

The Egyptians were aware of the richness of their land and

its life-giving river, and they were intimately attached to

it. According to them, there was no place like home. Not surprisingly,

the recurrent motif in Predynastic art, as seen on decorated

ceramics, was a boat with many oars and a deck cabin. Additionally,

hunting and pastoral scenes as well as vegetal motifs displayed

the richness of the Egyptian fauna and flora.

However,

this does not imply that the ancient Egyptians were totally

devoid of foreign contact. On the contrary. Egypt maintained

commercial contacts with its neighbours, Mesopotamia among

others, and the influence of such contacts can be seen in

art of the Predynastic period. A typical Mesopotamian motif

borrowed by the Egyptians can been seen on wall paintings

and on artefacts, such as the ivory handle of the so-called

Gebel el-Arak knife (Louvre Museum, Paris): the man wrestling

two beasts. Although the Egyptians borrowed a few artistic

elements from their northeast neighbour, they had already

begun to culturally and artistically define themselves and

develop a style that could be identified as typically Egyptian.

Indeed, the artistic conventions adopted during the later

part of this early period were to regulate Egyptian art for

the next 3000 years.

Following

the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, in spite of the

regular commercial ventures abroad, foreign motifs were almost

never used in the next three millennia of intense artistic

activity. Instead, internal politics, periods of economic

prosperity as well as social and religious values were to

influence art. Expectedly, the art of the Old Kingdom reflects

the economic prosperity of the country and the skill of the

artists trained in royal workshops while the crude sculptures

and paintings of the First Intermediate Period are the result

of a country stricken by famine and civil war, where untrained

artisans imitated to the best of their ability the art of

the previous epoch.

Yet,

the most incredible change of artistic values occurred during

a very prosperous age (end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, New

Kingdom), at the instigation of Pharaoh Akhenaton (Amenhotep

IV), the heretic king. Akhenaton favoured the cult of the

solar disk Aten above Amun, the national god, and all the

other deities of the Egyptian pantheon. Serious changes in

the artistic repertoire and Canon of human proportions thus

resulted from Akhenaton's reign and this religious revolution.

Egyptologists refer to this interlude as the Amarna period.

King

Tutankhamun, and the last pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty,

who ruled after him, reinstated the traditional artistic norms

and former religious beliefs. Despite the Amarna interlude,

New Kingdom art equalled and, according to many, surpassed

in quality and beauty the masterpieces of the Old Kingdom.

The

Late Period, which is often considered a period of decline

because of the decentralisation of imperial power, competing

dynasties, and various invasions, nevertheless reveals that

many of the rulers kept the ancient traditions alive, inspired

by the glories of the past.

As

Alexander the Great conquered the Near East, a wave of Greek

influence followed him. Egypt, which had initially inspired

Greece (Hellas), was not immune to Greek (Hellene) influence.

Hellenisation of Egyptian art was more or less subtle, yet present.

Later Roman influence, however, was more than obvious.

(Caroline

Rocheleau)

|

|