| Development

of Ancient Egyptian Art |

Artistic

Conventions, Canon of Human Proportions and Colours

Rigorous

application of artistic conventions have helped create "typical"

Egyptian art that remained virtually unchanged for over three

millennia. Naturally, the sculptor (the 'one who causes life')

and the draftsman (the 'scribe of forms') followed different

sets of artistic conventions with regards to their art.

Artistic

Conventions

Paintings,

sculptured reliefs, engravings, and drawings - referred to

as two dimensional art since they are produced on flat surfaces,

whether papyrus, plastered walls, flat rock outcrops, or nicely

cut stone walls - followed specific rules dictating how to

draw the human body. Egyptians did not depict the body as

they saw it with their naked eyes, but the way they thought

corresponded to the truth, the way each body part was clearly

identifiable. Such rendition of the human figure may appear

extremely strange to us, yet, to the ancient Egyptians, these

were very logical conventions: the head was drawn in profile,

but the eye and the eyebrow were depicted in full view. Men's

shoulders and upper torso were also depicted frontally so

that the arms, hands, and fingers were visible as well. The

belly and the waist were shown in three-quarters putting the

belly button not in the middle of the stomach but more to

the side of the figure. The posterior, legs, and feet were

shown in profile thus balancing the head. The feet were always

depicted from the inside, thus showing the arch of the foot,

but from the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty onwards, the Egyptians

preferred showing the outside of the foot. Needless to say,

such contortions are absolutely impossible! Women's anatomical

perspective differed slightly since the artists had to show

the body from the under the arms all the way down to the feet

in profile in order to make apparent the breasts. Exceptions

were rare but nevertheless occurred sometimes to facilitate

a certain movement of the arms. An interesting exception was

the dwarf god Bes, who was depicted in two-dimensional art

with his face seen from the front, just like in sculpture.

|

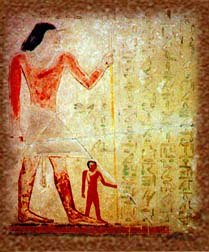

Metchetchi and his youngest son from the 5th Dynasty

found at the Royal Ontario Museum

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

Egyptian

sculpture (three-dimensional art) has often been described

as static, very cubic, and constrained. Ancient Egyptian statuary,

unlike ancient Greek statues, had limited numbers of position

in which people could stand, sit, or kneel because artists

did not free the sculpted form from the block of stone. They

rarely created voids and spaces that would create a lighter

and more expressive sculpture. Whether this was typical Egyptian

artistic expression or, as a famous Egyptologist recently

said, the effort of an elite to define and sustain an ideology,

scholars have no explanation. However, it must be said that

wooden sculptures made of composite pieces (body parts that

could be attached to the torso like a big 3D puzzle) allowed

more possibilities of positions. Possible reasons for these

more lively sculptures may reside in the fact that any damaged

parts (during the carving or later) could easily be replaced

unlike stone sculptures, which had to be entirely re-carved

should any accident occur in the workshop. By creating a more

cubic sculpture, the Egyptian sculptors certainly avoided

the breaking small thin sections and parts easily. Statues

are primarily to be viewed from the front, although there

are a few exceptions notably the statue of King Pepy the Second

and his mother. There were fewer conventions regarding the

actual representation of the human body in three dimensions.

Sculptors depicted the body the way it really was, without

contortions.

Statue of Vizier Kai from the 5th Dynasty found in

the Musée du Louvre

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

Except

for a few cases, ancient Egyptians were depicted in a more

or less idealised manner, the way they would have wanted to

be for the rest of their eternal lives. The majority of the

time they are beautiful, young and slim, however there were

many occasions where a person was depicted both as a young

adult and as a mature person in their tombs. Signs of maturity

were a more plump stature, a longer kilt, and the person wore

no wig. People were, in some instances, depicted as being

corpulent - whether as true to nature or as a sign of prosperity.

The most impressive sculpture of corpulent man must be the

statue of Hemiunu, a royal architect, vizier, priest, scribe

(among his many titles) who worked under King Khufu's (Fourth

Dynasty). The statue (Hildesheim, Germany) must absolutely

be seen, since it is exceptional in its physical rendering

of the man, its skilled execution, and its incredible size

(it weighs around 2 tons, if I am not mistaken).

King

Akhenaton's figure also is another exception to these artistic

rules. His elongated cranium, drooping features, long neck,

pot belly, large hips and thighs, spindly arms, and short

legs are so surprising that Egyptologists have been debating

for years (and many more to come) as to the exact reason for

this caricature and strange portraiture. It must be said though,

that, in spite of the unexpected figure, Amarna art generally

conforms to regular artistic and colour conventions.

Kings

were clearly identifiable in art, as they stood much taller

than the rest of the humans, and approximately the same size

as the gods depicted in the same scene. Evidently size served

to emphasise the divine office, the social status and power

of the king. Occasionally, queens were represented as tall

as their husbands, suggesting their own importance. More often

than not, though, women - all women, queens included - were

depicted rather small, barely taller than children.

|

|

Yet,

females in ancient Egypt seem to have enjoyed much more power

than their likes in Greece or Rome. Furthermore, kings sported

royal garments and accessories, such as a variety of crowns

with a cobra (uraeus) on the brow, special kilts, a false

beard (held to the chin with a string), and crooks, flails,

and other sceptres.

Famous

Queen Hatschepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty, even though a

woman, was depicted wearing the same accoutrement since she

was the actual ruler. Queens' regalia were much simpler, although

their regal appearance is obvious. The most famous headdress

worn by royal women is undoubtedly the vulture headdress with

the vulture's head on the brow and the wings on either side

of the ears. Queen Nefertiti (Akhenaten's wife) also wore

a unique tall blue coiffe.

Depictions

of children, royal or not, in Egyptian art also followed specific

rules. Children are easily recognisable by the simple fact

that they were depicted naked. Needless to say, Egyptian children

did wear clothes, as proven by very small garments found in

archaeological excavations. Nudity, in this particular case,

indicated the young age of the child. However, adults were

sometimes depicted naked, as a symbol of rebirth in the Afterlife

(in the case of a funerary statue) or simply because certain

tasks were better performed without clothing impeding movements.

Small children, in addition to being naked, were shown with

their index finger on their lower lip, not unlike our own

children sucking their thumbs, as well as sporting the 'side

lock of youth,' a braid of hair worn usually at one side of

the head. Adolescents, on the other hand, were represented

wearing full clothing and adult hairstyle or wigs. Yet, just

like small children, they were depicted much smaller than

their parents were, sometimes barely keen-high, no matter

how tall they really were.

|

Pepi the Second and his mother from the 6th Dynasty

found at the Brooklyn Museum

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

Interestingly,

these conventions did not apply to Pepi the Second, a six-year

old who became the fifth king of the Sixth Dynasty. Unlike

boys of his age, little King Pepi was not represented naked,

he did not sport the side-lock of youth, nor did he have his

index finger on his lower lip. The magnificent alabaster statuette

from the Brooklyn Museum shows Pepi sitting on his mother's

lap wearing his royal regalia. Decorum would not allow that

King Pepi, even though a young child, to be depicted like

other boys his age. Nonetheless, he is represented as small

as other children would be, with his mother holding him protectively.

Children

and adolescents either stood or sat quietly at their parents'

feet or accompanied them in various family activities. The

former docile behaviour was typically rendered in statuary

since artists had much less choice in their composition than

in paintings or reliefs, were they actively participate in

the action of the scene.

Canon

of Human Proportions

The

Canon of Human proportions was a square-grid of 18 units applied

to a drawn human figure (standing) allowing its reproduction

in various sizes, but always anatomically proportionate. There

were 2 squares allowed for the face (from the hairline to

the base of the neck), 10 squares from the neck to the knees,

and 6 squares from the knees to the sole of the feet. There

was a nineteenth square used for the hair, but it was not

counted with the rest of the body. A sitting figure was divided

into a 14 square-grid (15 including the hair). Not surprisingly,

the Amarna artists (Eighteenth Dynasty) had to used a different

square-grid of twenty units. The usual 6 units were kept between

the sole of the feet and the knees, but two extra squares

were added to the between the knee and the neck, creating

shorter lower legs and a longer neck if one of the squares

had been added to the neck rather than the torso.

These

square-grid divisions corresponded to general human proportions,

although Akhenaton's physical appearance is still the subject

of hot debates among Egyptologists. Nevertheless, the 18 unit

square grid remained in use until the Late Period, when the

Twenty-Sixth Dynasty adopted a square-grid of 21 and a quarter

units that was in used until the end of Pharaonic civilisation.

The same square-grid was also used in statuary and pale red

lines can still be seen on some unfinished reliefs, painting

and sculptures. The concept of the square-grid is still used

by architects, draftsmen, designers, and artists nowadays.

Colours

Ancient

Egyptian artists had a very limited palette of colours: red,

blue, yellow, green, white, and black. The symbolism of each

colour is best left unexplained at this moment as some colours

are interchangeable and colour conventions are not yet fully

understood. Although the Egyptians favoured strong, pure colours,

skilled artists sometimes worked with mixed colours such as

grey, pink, brown, or orange. Imagining all sculptures and

reliefs painted with bright, vivid colours is quite a task

for the imagination, especially since few fully painted monuments

have been uncovered by archaeologists. Yet, all the statues

and sculptured reliefs were entirely covered with thick, rich

colours, despite the inherent beauty of the stone from which

it was carved.

Paintbrushes, Pigments and Palette found at the Royal

Ontario Museum

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

Along

with the artistic conventions and canons of proportions, there

were colour conventions for artists to observe. The most interesting

colour convention was based on gender distinction. Ancient

Egyptian males were always painted in reddish-brown tones

while females had a pale yellow (sometimes pink) coloured

skin. Such colour distinction was partly symbolic of men and

women's lifestyles. Men led a more active, outdoor life as

opposed to the indoors life of women. Old men, and this is

noteworthy, were often also depicted pale skinned, symbolising

old age and a more sedentary lifestyle.

(Caroline

Rocheleau)

|

|